How To Choose Fretwire

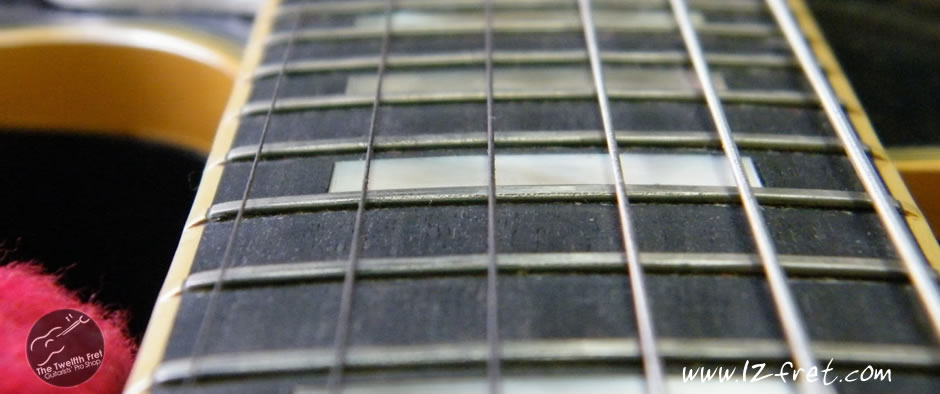

You like your instrument and play it a lot. Now, you’ve come to the point where the frets are worn enough that you need to consider whether to dress and re-crowned, or re-fret. If they can be dressed, this lasts for a while. But if they’re going to be replaced, what kind of fret should you choose?

Fret choices used to be easy because little was available and even that was hard to find. Fret wire was wider and low (Gibson) or narrower and low (Fender), or even narrower and low for mandolins and banjos. Classical fret wire was a bit different, a medium width with some height, but soft.

At some points, many people thought that worn-out frets meant you had to replace a neck. Now, there is a bewildering array of readily available fret wire, sold through major suppliers like Dunlop, AllParts and Stewart-McDonald. Re-fretting is now a common task in any repair shop.

We’ll try to make some sense out of why you might choose one over fret wire over another.

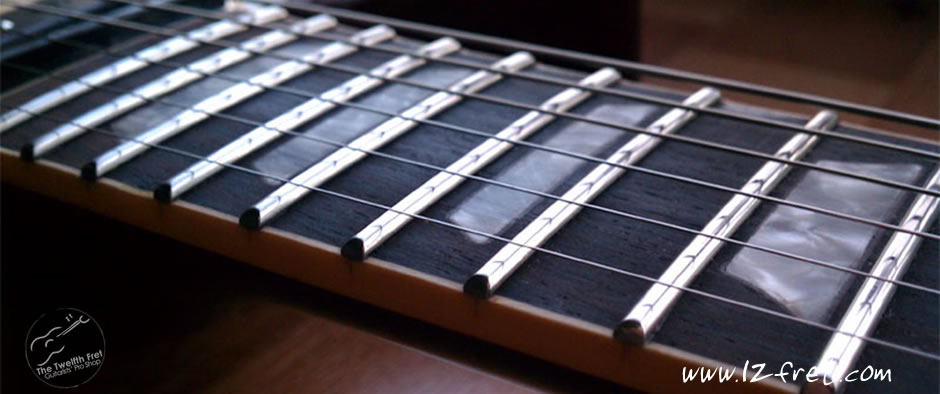

Originally, frets were pieces of gut tied around the neck, and some renaissance instruments like lutes are still built this way. Later, bone, ivory or metal strips were inlaid for a more secure positioning. When metal, these were called ‘Bar Frets’ and were used until the 1930s. Modern fretwire with a distinct crown and tang appeared in the 1890s. The crown is the portion you see on the fingerboard. The tang goes into the fretboard slot and has teeth to provide grip. This design ensures that there is always material above the surface of the fingerboard and provided it’s just deep enough, the depth of the slot isn’t critical.

On modern crowned frets, there are four meaningful dimensions: the tang depth and width and the crown height and width. The two tang dimensions dictate how deeply and wide the fret slot is cut.

The crown size is most relevant to players. A low crown is often part of the original feel of a vintage guitar, especially those from periods where string bending was seldom if ever used. Gibson used the marketing term ‘Fretless Wonder’ for the Les Paul Custom, because the frets were ground very low, with the action to match.

For the modern player, new styles of fretwire with a higher crown are more practical and new materials are available. There are several advantages.

First, the larger amount of metal takes longer to wear away, so there is more time between re-frets, and worn frets can be levelled and shaped or re-crowned several times.

Second, the added height provides a more positive feel making it easier to bend and harder to ‘drop’ the string mid-bend. At one time, players often expressed interested in scalloped fingerboards for extreme bending, but the availability of very high fret wires makes this almost un-necessary. The grip that many players are comfortable shifting to a higher gauge string.

Third, with more mass at the end of the string, the note can be clearer and sharper, with more definition between tones in a chord.

Fourth, establishing a definite center is easier on a high fret, which aids precise intonation and tuning. A low fret may not have enough material to shape the high center, so the string can wind up a detectable distance from the carefully calculated fret slot.

Finally, the new fret materials are more durable and hypoallergenic.

Higher frets offer several advantages, but they can take some getting used to. Very high wire makes the action look higher than it really is. The eye sees the distance from the string to the fingerboard surface, but the string stops at the top of the fret. The hand and the eye ‘see’ differently, and the eye can want the hand to press the string to the fingerboard.

How To Choose Fretwire

A player used to low frets often develops a habit of gripping the neck tightly. With high frets, this grip will send the notes sharp, especially on chords which careen out of tune. It’s necessary to learn to relax the fretting hand, which will also relax the picking hand. This relaxation also reduces fret wear, because there’s less grinding effect by the string on the fret.

Fretwire has both height and width. Narrow fretwire is very appropriate for short-scale instruments like mandolins, where the upper frets are close together, but it was also common on vintage Fender style instruments. However, narrow high frets can feel quite ‘bumpy’, so a wider high fret can be more comfortable to play.

In the last few years, new materials have been introduced. Fret wire was once produced in relatively soft metals including brass for ease of use, at the expense of longevity and tone. The most common fret wires are now made of silver-free ‘Nickel Silver’ or ‘German Silver’, a compound of about 80% nickel and 18% copper with the last 2% being small amounts of metals like zinc and cadmium. This material is easy to work with and is available in many sizes, but some people have allergies to nickel.

How To Choose Fretwire

Stainless steel wire has been introduced for some popular fret sizes, and it is very durable and crisp-sounding. However, its hardness requires special installation tools and may transfer the wear to the strings instead of the fret. Expect to pay more for a re-fret with stainless wire, simply because it is harder to work with.

In the middle is EVO fret material made by Jescar, originally created as a hypoallergenic, nickel-free material for eyeglass frames. EVO wire has a gold tint and is almost as hard as stainless but almost as easy to work with as standard ‘nickel-silver’ wire.

If you need to replace frets, your local repair shop should have samples of the various sizes. Try out new guitars that use the frets you are interested in, to get a real sense of how they will feel.

Patrick Keenan